by Nika Levikov (University of Malta)

The premise of Soapbox — an ongoing event that began last year to promote the quarterly THINK magazine published by the University of Malta (UM) — is simple: to communicate the diversity of research happening on and off campus. Intrepid researchers and academics who are daring enough to discuss their work in front of a slightly tipsy audience have a few minutes on a soapbox to communicate what they do (think TED meets speed-dating). Then they stand awkwardly as the host opens the floor to questions – any question, or statement, which in the past have led to heated debates. I knew what I would discuss: responsible research and innovation (RRI). Rather than focusing on the NUCLEUS Project study the UM team (composed of Dr Edward Duca, Daniela Quancinella and myself) is investigating, I spoke about the concept itself: linking academia with society.

Research has evolved in significant ways over the centuries. Darwin needed a long time to do his work, and he withheld it for a long time too. Newton was notoriously suspicious and kept most of his work a secret. Since then, the research process has become more collaborative and accountability is crucial. Furthermore, alongside drastic increases in the pace of research, scientists are now expected to be excellent communicators, grant writers, project managers and administrators. Making everyone work quickly and openly does have its downsides, so what are the upsides, I asked?

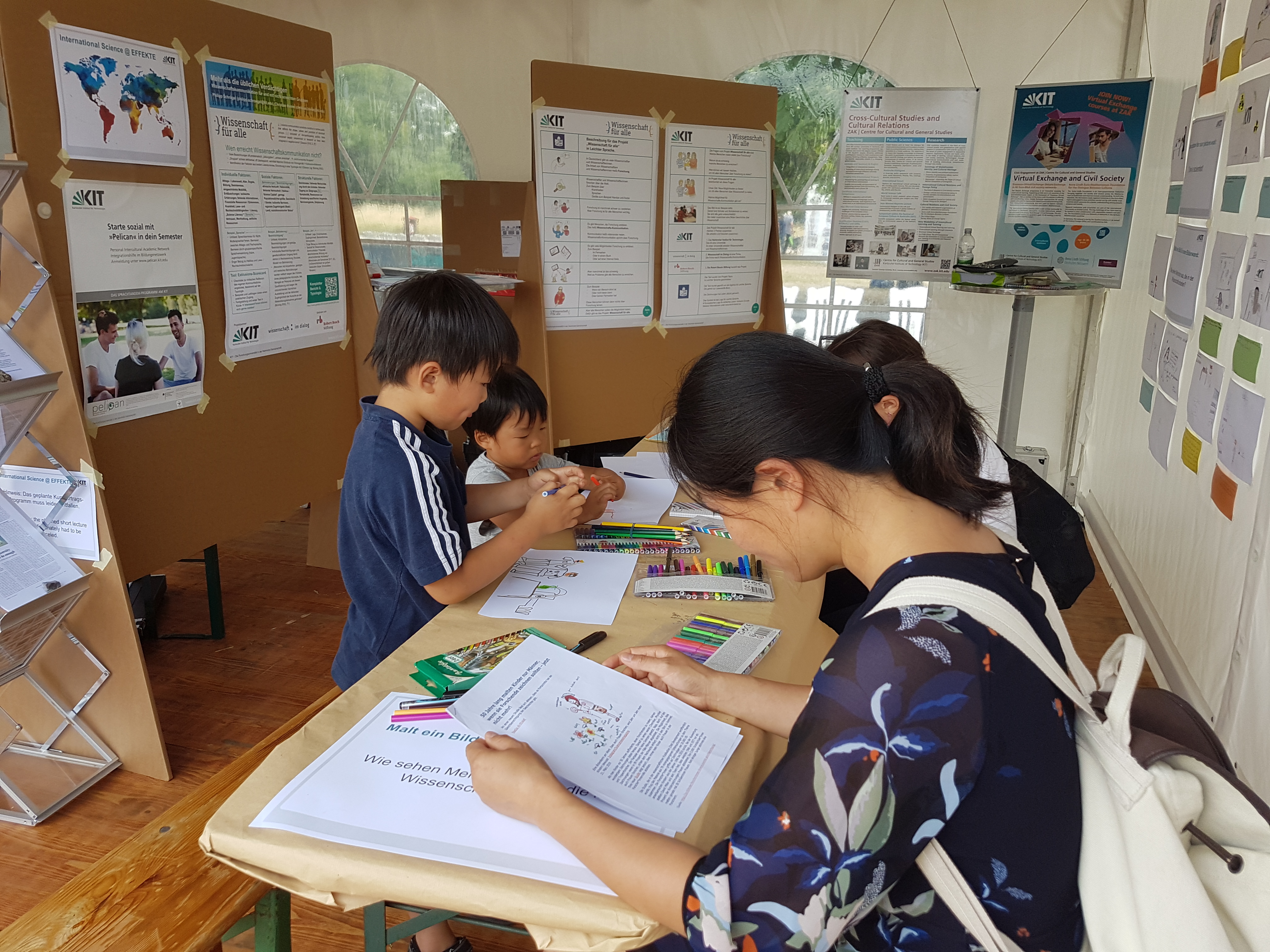

One of the spectacular ways in which research has advanced, I believe, is in understanding the value of collaborations and connecting with society, in bursting the academic bubble and opening research to the world. Some argue that it is unrealistic to expect a physicist to engage the public when, after all, how do you get a group of citizens to comprehend and get excited over things like quantum theory? Or that the uphill struggle in making material easily digestible and engaging is not worth the time. Yet many professionals in the academic sector and the EU itself argue that it is now part of the job. This means we are recognising the importance of transdisciplinary collaboration and research, as well as how publics can inform what we do and how we do it.

Studies have shown that creative and innovative solutions are often made when different stakeholders with a diversity of backgrounds come together to solve a problem. We want society to be involved in the research process, for them to know that ultimately, research is not just about pursuing individual interests, but also to give back to surrounding communities. The UM is in a position to do so given it is a public institution funded by the government. In other words, my salary is literally coming from taxpayer money. I have a duty to put societal needs at the forefront of my work. As do all researchers.

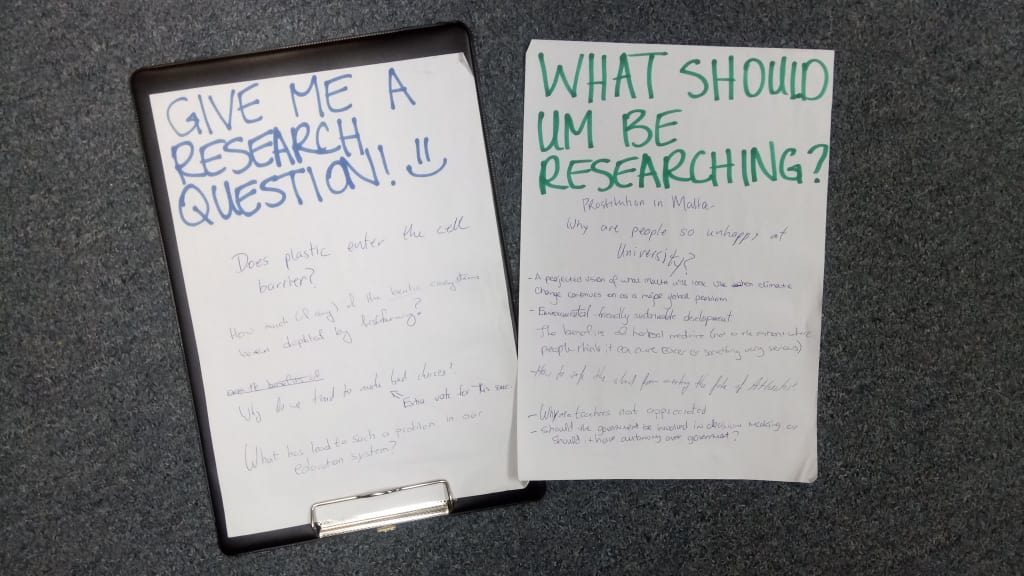

Nearing the end of my talk, I pulled out a clipboard with a question: ‘What research should UM be doing?’ If we are to engage with society beyond standard practices of outreach, such as a public lecture covering results of a study, then we must be active in implementing creative activities and informal learning events. Society should be helping us shape research questions, I said. Everyone’s voice is important.

After making fun of myself for writing the questions so aggressively on paper, I passed two sheets around. The responses covered a range of topics, from environmental concerns to deceptively simple – yet in reality very complex – questions about our wellbeing. Some questions have been addressed by already existing research, such as, “Why do we make bad choices?” and “How much life (if any) of the benthic ecosystems [has] been depleted by fish farming?” Inevitably, questions were raised pertaining to the local climate, including requests to address sex work and a perceived lack of appreciation of teachers in Malta.

The questions were written by educated hands, some of which belonged to native Maltese and others, like me, who have migrated from other parts of the world. Since the event, I have wondered what kind of questions would be asked from those who have not experienced tertiary education. What would an aging Maltese farmer want to know and is there something we can investigate together that would enrich both our lives?

At UM, we are working to facilitate constructive dialogue between society and academia, and there is still a long road ahead. The responses from the audience during Soapbox provided only a sliver of all the curiosity, issues and concerns that face modern day society. But perhaps one day, the external stakeholder and lay person sitting next to a researcher playing with ideas will be so commonplace that exclusion, the “bubble” will be a reference to a more conservative time long, long ago.

It’s on some of these informal meetings or gatherings that one can get to know social science aspects of a community, or locality for this matter.

Research itself has grown so much, with more people wanting to collaborate more than others, with more researchers keeping their valued data sets close to their loins more than others.

Interesting suggestions your people were giving on the research topics.

Well done!

Thank you very much, Lemaiyan!